This is an old revision of the document!

Primary Keys to Classical Music

1.0 Introduction

In any data-based application, the key to flexibility, speed and extensibility is to be able to identify, with the fewest possible pieces of information, an utterly unique way to find a single piece of data in which we're interested. The combination of attributes which uniquely identify a data item is then called the 'primary key' of that particular data set.

Technically, the problem of how to find the minimal primary key to retrieve needed data is a branch of “information theory” -but this detail needn't detain us unduly and I promise to try to make the discussion as un-technical as possible. So long as you remember that “primary key” means “least information needed to retrieve the full set of data”, you're doing fine!

In any event, the point of this article is to examine the question: If we are to catalogue our music so that it can be accessed flexibly and quickly, what is music's 'primary key'? Having identified it, do the practical restrictions placed on us by common music playing software cause us to re-think it in any way?

In this article, then, I'll explain what music's primary key is and how the distinction between 'primary' and 'secondary' types of data about music is an important one to remember as you practically go about cataloguing and classifying a large music collection.

2.0 An example with Books

To begin with, I'd like you to think about how you identify a given instance of a book or novel? (I don't mean distinguish between different copies of a book; just between two different novels in principle). In many cases, you might think 'book title', since you would not then confuse A Tale of Two Cities with, say, Dombey and Son -and, in many cases, this would indeed be unique. But therein lies a trap, because book titles are only usually unique, but they don't have to be (see this article for some good examples of where book/novel titles have been duplicated (or nearly so) over the years). First rule of information theory: if it's ever possible for a data attribute to be non-unique, it cannot on its own be used as a true primary key. It doesn't matter if, in a particular set of circumstances, the data attribute is unique. That is, I walk into a specific book shop and find that they don't have a copy of Kate Acker's Great Expectations, so in that shop, book title is unique. No matter. The fact is that, theoretically, the title might duplicate in another bookshop. Therefore, book title cannot be a primary key candidate.

To work around that requirement, perhaps, we'd think, “Add in Author. The combination of Author+Title must surely be unique?” Certainly, Charles Dickens+Great Expectations is now easily distinguished from Kate Acker+Great Expectations, so the combination of Author+Title seems unique enough to warrant being thought of as a book's 'primary key'.

However, we must again consider the context within which a primary key will be used. For example, consider my own bookshelves at home: I'm lucky enough to own an 1848 first edition of Dickens' Dombey and Son. It's lovely to own… but it's got lots of typographical mistakes, the pages are quite brown and the font used is rather old-fashioned. So whilst it's nice to own it, I never actually read it! For that, I have the Penguin Classics paperback edition…at which point, my bookshelves violate the uniqueness of Author+Title, for there are two Dickens+Dombey and Sons on my bookshelves!

There are various workarounds possible. The first one that springs to mind is to add the publishing house. OK, let's try that then: my first edition appears to have been produced by Bradbury & Evans; the paperback by Penguin. Charles Dickens+Dombey and Son+Penguin does now seem distinguishable from Charles Dickens+Dombey and Son+Bradbury & Evans. Primary key re-discovered, then!

Well, maybe not so fast: Penguin have re-printed their version of the novel many times over the years, I'm sure. The one I have is dated 1995… maybe there's a 1996 printing of the same edition? It's unlikely someone would have both copies on their bookshelves at the same time, of course… but if it could happen, then we cannot consider Author+Title+Publisher a truly good primary key candidate. Maybe we'd have to go for Author+Title+Publisher+Year instead, then?

In this manner, we could continue to explore and add new pieces of information into our primary key candidate until we hit upon some combination or other that is truly and forever unique, in a particular context: that would then cease to be our primary key candidate but would become our actual primary key.

I won't pursue this particular line of thinking further, because I frankly don't know enough about the printing and publishing trade to really tell you what an ideal primary key would end up being! I really just wanted to show you that your first thoughts on a likely primary key candidate are seldom the last word on the subject: as the scenarios and possible situations in which your data model must work proliferate, so what seemed like good keys turn out not to be so good at all. And what might work well in one situation might fail badly in another (for example, consider if your bookshelves do not have two versions of Dombey and Son on them, but mine do: what you decide is an excellent primary key might then be a disastrous choice for me in my environment).

I also wanted to make the point that what we think of as candidate primary keys have no relation to other things we might want to find a novel by. I mean, for example, that I may well think to myself one morning “I wonder what novel it was that had the line 'It was the best of times; it was the worst of times'. That is an entirely valid question -meaning, it's an entirely legitimate thing to want to search for. But 'by their first lines' is not a suitable way to organise the fundamental ordering of a catalogue of books (because they could, plausibly, duplicate… and first lines are always going to contain more words than the terse combination of author+title+publishing house name. Remember: we are seeking to minimise the criteria that define uniqueness). The need to order a data set in such a way as to find unique items comes first; the ability to search data for any random thing that springs to mind is a secondary (though important) consideration. The requirements of the latter should not dictate how we determine the former. Searchability is a different problem domain than sensible ordering, basically.

3.0 Natural and Synthetic Primary Keys

I also want to pause at this point to say that what I've been describing is the finding of a natural primary key: that is, a key using pieces of information (such as an Author's name, or a novel's title) which make natural sense to humans. There is often an easier way to devise a primary key, however: use a synthetic primary key. That is, pick a piece of meaningless data which makes no real sense in the outside world but which you know, because you invented it, will be unique for every data item and label each data item with it. For example, every time you open a spreadsheet, you're looking at a synthetic primary key in the far left-hand column of the screen: the row numbers start at 1 and increment sequentially thereafter. Every row in the spreadsheet is therefore 'addressed' (and can be referenced by) a guaranteed-unique number which in and of itself has no meaning or significance to the data you choose to store in the spreadsheet's cells. If I say 'see cell A1', you might be about to read your name or your salary or someone's address: “A1” uniquely identifies the actual data, but bears no relation to that data, in and of itself. That is the essence of a synthetic primary key.

Books essentially have such a synthetic primary key ready-made for them these days, too: the ISBN (the International Standard Book Number). It doesn't identify every individual copy of a book uniquely, but it identifies a particular printing/edition/variation of a book. So Penguin's print of Dombey and Son will have a different ISBN to Random House's print of the same title, and so on. Of course, the ISBN was invented after Dickens died and my first edition of the novel accordingly doesn't actually have an ISBN… which kind of scuppers using it as a truly universal primary key! But if we said 'what's the primary key of books printed after 1970?', the ISBN would be a fine candidate.

Anyway, the point is that synthetic primary keys are easy to make 'guaranteed unique' and completely immutable. But, being synthetic, they lack meaning for real people! You don't often go into a bookshop and say, “Do you have a copy of 968-3-16-148710-0, please?”, for example! Thus, whilst they are great for defining uniqueness, they are pretty lousy for using in real life. As such, I want to restrict our thinking here only to natural candidate primary keys from now on.

4.0 Printed Music's Primary Key

So now let me re-phrase my initial question: what is the minimum combination of attributes that will uniquely identify a given piece of printed or hand-written music in natural form? I don't mean CD or DVD music at the point: I simply mean, how do I tell the difference between this symphony and that one, or this piano concerto and that one?

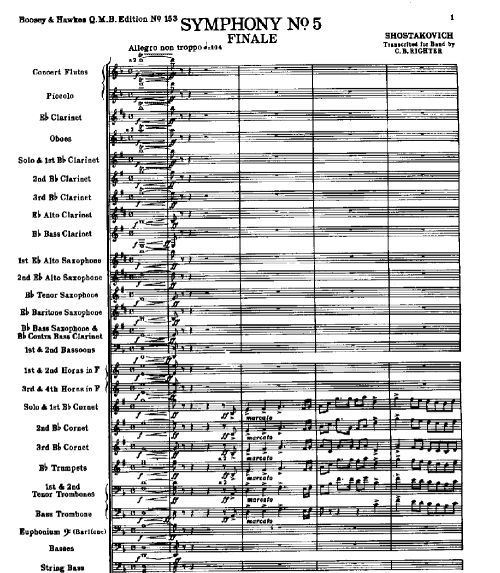

Well, it cannot simply be the name of the composition. Here's a Symphony No. 5:

… and here's a completely different Symphony No. 5:

How can we tell them apart if their names are identical? I think it's easy to see that composition name is not and can never be a candidate to be music's primary key, therefore.

But what if we add in the Composer's name? Would Beethoven+Symphony No. 5 be unique and forever distinguishable from Shostakovich+Symphony No. 5? I think it might well be. The questions to ask to make sure would be: did a composer ever compose a piece of the exact same name twice or more? Unfortunately, I'd then remember that Gustav Holst wrote two completely different compositions called A Somerset Rhapsody and Johann Sebastian Bach wrote two completely different pieces called Prelude in C major …these days, they get given distinct BWV catalogue numbers, but in Bach's own day they would not have been distinguishable by name alone. John Field similarly wrote two distinct Nocturnes in B♭ major… so, at this stage, it's fairly obvious that Composer Name+Composition Name cannot be printed music's candidate primary key!

It gets even worse if you shift the context a bit and ask how you uniquely identify the various parts of (say) a symphony. With Beethoven's Fifth, you could easily distinguish the Allegro con brio movement from the Andante con moto, for example… but don't try that trick with Mozart, who was frequently rather unimaginitive when giving his movements tempo markings: his Symphony No. 11, for example, has movements labelled Allegro, Andante and Allegro: so now try and distinguish between the first and third movements?

Well, this one is not easy to fix, to be honest, without resorting to a little synthetic key trickery! If we add a movement number into the mix, we'd end up with: Mozart+Symphony No. 11+1+Allegro and Mozart+Symphony No. 11+3+Allegro …and those two things are actually unique and distinguishable from each other.

So now our primary key candidate is: Composer+Composition+Movement No.+Movement 'title'

I'll pause at this point to mention that this is actually not a robustly good data model from a strict information theory point of view, since the last component of that candidate key is actually and merely what is called 'derived information'. If you tell me “Mozart+Symphony 11+Movement 1”, I actually already know (or, at least, could look up in Wikipedia to find out) that the movement's tempo indication is 'Allegro'. Similarly, mentioning 'movement 2' would tell me, by implication, 'Andante'. Technically, there's no need to include derived information in a primary key candidate, since the piece of data which gives us the ability to derive that extra piece of data is already sufficiently unique.

Put it another way: by introducing movement number into the mix, we've technically done the same thing as quoting row numbers in a spreadsheet: it's already unique; adding the movement name after that doesn't actually help us get 'more unique' than we already are!

Thus, technically, we only need three pieces of data in our primary key candidate: Composer+Composition+Movement Number. Would these three pieces of information be a good primary key candidate, though?

Technically, yes, I think so. But… but… no-one of mortal woman born actually remembers the tempo markings associated with every one of Haydn's infeasibly large collection of symphonies. If I said “Haydn, Symphony 34, Movement 2”, would you happen to know in passing that I meant the Allegro from that symphony? Probably not. Moreover, would it be of practical use to know the movement's tempo marking? Yes, it is, I think. So, practically, though it's not needed from a data theory point of view, I'd definitely want to include 'movement name' in the proposed primary key. Strict disciplinarians of data modelling would call this 'a flaw in the normalization of the data', but sometimes practically takes precedence over purity!

So, four data attributes are practically required for music's primary key: Composer+Composition+Movement Number+Movement Name.

And I think that's a good primary key candidate for music in its printed or hand-written form. With it, I think we can distinguish between a Haydn symphony and a Beethoven one; or a Beethoven one and a Shostakovich one. We can also tell the 15 Shostakovich symphonies apart from each other. And we can tell Shostakovich's Symphony No 1's Allegro movement (movement 2 of that symphony) is different from Shostakovich's Symphony No. 10's Allegro movement (also movement number 2 of that symphony). Some part of the Composer+Composition+Movement number+Movement name combo is, it seems to me, always unique in all those situations, so I think it's not just the candidate primary key, but the actual primary key for printed classical music.

5.0 Recorded Music's Primary Key

So, we have our primary key for classical music. Case closed? Well… not so fast. When we get to recordings of classical music, I think what we've worked out so far turns out, rapidly, to be unworkable. In other words, let me change the context once more: no longer am I trying to buy a score of a symphony from Boosey & Hawkes: now imagine I'm trying to buy a CD of a symphony from Amazon. Our primary key thus far is completely unworkable, for the simple reason that although Beethoven wrote only one Symphony No. 5, it's been recorded about 12,200 times by assorted conductors and orchestras around the world in the 90 years or so since recording technology made that sort of thing possible.

So if the 'uniqueness context' is now the ability to tell apart Bernstein's recording of Symphony No. 5 from Karajan's, our earlier primary key is not up to the job: Composer+Composition+Movement Number+Movement Name is no longer capable of telling one recording apart from another.

Clearly, what we need to add to the mix is the conductor's name. If we had: Beethoven+Symphony No. 5+1+Allegro con brio+Bernstein we'd easily tell that apart from Beethoven+Symphony No. 5+1+Allegro con brio+Karajan, wouldn't we?

Well, we would…except that the two conductors I just mentioned had a habit of recording the same symphony multiple times! Karajan, for example, recorded Symphony No. 5 five times in less than 40 years. How do you tell his 1950s recording of it apart from his 1962 recording? Or Bernstein's 1961 one from his later effort in 1976? Well, the question rather prompts the answer, doesn't it? If we were to stick a recording date in our candidate primary key for recorded music, those sorts of 'repeat recordings' would be uniquely distinguishable from each other. That makes our candidate primary key for recorded classical music: Composer+Composition+Movement Number+Movement Name+Conductor+Recording Year.

Unfortunately, the next question is equally prompted: did a conductor ever record the same composer's composition in the same year more than once? Well, it's a pretty rare occurrence, I think… but it's not unheard of. Klemperer recorded Beethoven's Ninth symphony twice in 1957, once in the studio and once in a concert at the Royal Festival Hall. Likewise, Toscanini recorded the Scherzo from Mendelssohn's A Midsummer Night's Dream twice in 1929. So, it's quite primary in nature, but it's not perfectly so. To get around the rare exceptions, perhaps we could guarantee that our primary key would cope by borrowing from the synthetic world of the spreadsheet once more. If we made the candidate key the following:

Composer+Composition+Movement Number+Movement Name+Conductor+Recording Year+Recording Number

Then you'd be able to distinguish “Beethoven, Symphony No. 9, 2, Molto vivace, Klemperer, 1957, 1” from “Beethoven, Symphony No. 9, 2, Molto vivace, Klemperer, 1957, 2”. You wouldn't need that recording number differentiator in nearly all cases, but it's there should the occasion arise.

At this point, then, it would seem that the minimum number of data items required to uniquely identify a recording of a part of a composition is: seven. We finally have our answer!

6.0 An Intrusion of Practical Considerations

I want to pause again at this point. We now have arrived at an answer to our earlier question: to uniquely identify any individual track (i.e., movement) of an LP or CD, we appear to be proposing a 7-component natural primary key. The problem I have with that 'answer' is that whilst it seems a logically-robust answer, it's difficult to imagine working with that length of primary key in a very efficient or practical manner. We also have to intrude the theory discussion with matters of software practicality: would assorted software media players even be able to function with a 7-component primary key?

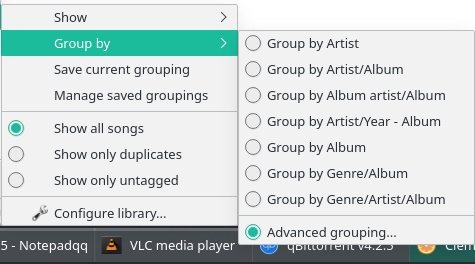

Take, for example, the Clementine media player (it happens to run on Apple, Windows, Linux, Raspbian and probably a few other operating systems besides, so it's a reasonable approximation for a 'universal' media player). How does it organise it's principal display of music? Like this:

Though there are seven built-in grouping options listed (select any one of them and that also becomes the default sorting order of your music library display), you'll notice that none of them allows for more than three identifying components? For example, “Group by Artist/Year - Album” and “Group by Genre/Artist/Album” both only offer three grouping and sorting data components. Nowhere is there a listing of a 7-component grouping function!

To be fair, “Artist - Year - Album” is sort of like the “Composer - Recording Year - Composition Name” elements of our proposed primary key, so we could usefully group (and sort) by three of our seven primary key components. Which is great -but means the remaining 4 would end up not being a grouping or sorting consideration, and that would break the functionality of the player. Looks like we're out of luck then, practically! Unless… Is anything available to fix this under that 'Advanced Grouping' option?

Turns out… not really:

Here, you certainly get to choose which three data items to group and sort by, choosing from drop-down lists, but three element grouping is still your limit.

This would seem to be a failing in Clementine -but you'll find most media players do the same sort of thing, largely because if they did allow you to sort and group by all seven primary key elements, the display would end up being an unholy mess. Think of it: you'd have a list of composers; click on one of those and you'd get taken to a list of compositions by that composer; click on one of those, you'd get taken to a list of all the movements belonging to that selected composition and so on. You'd have to click seven times before you got to a unique track of recorded music that could actually be played. Functionally, therefore, using such a long composite key would be a bit of nightmare.

Yet, theoretically, a 7-segment primary key still seems to be necessary.

Is there a resolution to this apparent paradox?

7.0 Paradox Resolved!

Summing up: We need 7 data elements to uniquely identify any specific piece of recorded music (down to the individual movements making up a symphony or concerto, or the individual arias or recitatives making up an opera, or the individual songs in a song-cycle). But, functionally, we need to restrict ourselves to just three. To cope with this functional 'restriction of three', we will need to combine some of our separate data elements into a single, aggregated data element. We should also remember that some of our primary key elements are actually derived information -so, strictly speaking, they don't need to be in the primary key at all.

So first, let's prune out the derived information: Composer+Composition+Movement Number+Conductor+Recording Year+Recording Number

…gone is the Movement Name as a piece of plain text. We're back to thinking just in movement numbers. We'll always want to see plain text names, of course; but we don't need to use them functionally in a grouping or sorting discussion. For one thing, symphonies would sound very odd if we played their movements in alphabetical order! So we're already down to just 6 key data elements -though that's still three more than we are allowed.

So now it's time for some combinations! If we move the conductor and recording year details up the hierarchy, we can achieve a useful bit of concision, like so:

Composer+Composition [Conductor+Year+Recording Number] + Movement Number

Think about it: if Karajan recorded something in 1961 twice, then all three of the elements I've put in square brackets there kind of travel together. They're all dependent on each other, in other words. You couldn't change the conductor name, for example, without that immediately implying the year and recording number were different, too. So that kind of implies that you could treat all three components as a single data entity, not as three separately-independent entities. This in turn means that we'd catalogue things as, for example: “Beethoven, Symphony No. 5, (Karajan 1962 1), 1”: that immediately takes us down to just 4 data elements, which is getting awfully close to the three we'd like to get it down to!

But we can go one step further: these 'conductor-year-recnum' elements are themselves sort of dependent on the composition name, not in reality (I'm sure Karajan conducted lots of things in 1962), but practically: Karajan recording something in 1962 is pretty useless information to have if we don't know what he conducted, isn't it? So, in that sense, knowing “composition+[conductor+year+recording number]” as a single piece of information makes sense.

What we'd be doing at this point is saying that a particular recording of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony is intrinsically the composition itself (obviously) plus the conductor and the year of the recording. The composition name ceases to be an independent item of data, but needs to be 'attached' to the name of the person recording it. I therefore refer to the result as the extended composition name: it's the 'regular' composition name that Beethoven himself would have known plus the conductor+recording year (and number, if needed). We then have to generalise a bit, because I'm sure you'll have recordings of works that aren't symphonies and maybe don't have a conductor: think of string quartets, for example. So rather than saying that the extended composition name is composition+conductor+year, we should say it's composition+distinguishing artist+year.

By “distinguishing artist” I mean: the person, or persons, who make this recording distinctly different from that one. It might be Karajan versus Bernstein; or the Amadeus Quartet versus the Maggini; or Callas versus Sutherland. It doesn't particularly matter who makes this recording distinguishable from that one, so long as it's an identifiable name.

I'm therefore proposing that you catalogue your recorded music in the form of, for example:

- Benjamin Britten - String Quartet No. 1 (Emperor - 2005)

- Gustav Holst - Symphony 'The Cotswolds' (Davis - 2018)

- William Walton - Henry V (Barenboim - 1977)

…and so on. Should necessity ever arise:

- Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphony No. 9 (Klemperer - 1957 #2)

Obviously, within each of these recordings, too, there'll be multiple movements that uniquely-numbered movement identifiers, to get us back to our threepieces of uniquely-identifying primary key data.

A subtle point here is that the extended composition name, including the distinguishing artist name, should always be used, even if it happens that in your collection at the moment there's only one recording of a work that doesn't really need to be distinguished from any other recording of it.

You might think, for example, “Since, I only have the one recording of Turandot, it's already unique in my collection, therefore I only need to mention 'Turandot', not 'Turandot (Callas - 1957)'”. Remember: the point of a primary key is to be able to uniquely identify data in any conceivable context. That you only own one Turandot today doesn't mean you won't buy another version of it in the future… and at that point, you'd have a differentiation problem if you hadn't already dealt with the primary key issue up-front. Put simply, this means you should always specify an extended composition name (and thus use a distinguishing artist name) for all your recordings.

The key point is that by constructing this extended composition name, we've just reduced the number of separate components required in our primary key candidate for recorded music to only three elements: Composer Name+Extended Composition Name+Movement Number. Clementine can cope with that as a default sorting and grouping arrangement: so can every other music player on the planet! What's more, it means there will never be more than three clicks needed to start playing a unique recording of something.

Job Done! … Or is it?!

8.0 A Modified Solution: Bring on the Genre!

So, the proposed cataloguing scheme for classical music is:

Composer → Extended Composition Name → Movement number

…where the “Extended Composition Name” is itself comprised of: Distinguishing Artist Name, Recording Year and Recording Number if needed.

This will work quite nicely, but it will get quite “chunky” at times. Benjamin Britten wrote only 93 published pieces in his lifetime, which is manageable. But J.S. Bach wrote over a thousand of them, which isn't. Mozart wrote over 600 of them, which is also unmanageable as an undistinguished lump of music! What I mean is that if you are scrolling through 93 recordings, that's fine; but trying to scroll through 1000 of them and hoping to pay attention to each one as they pass your glazed eyes is going to be a much tougher ask! Bear in mind, too, that for any given composer, if we sort by Extended Composition Name, they're going to be in alphabetical order, so your Cantatas will be at the top of the list and the Xylophone Concerto will be at the bottom: that's not a lot of fun if all you want to listen to is the Xylophone Concerto one day! If you have to scroll through hundreds of A, B and Cs to get to the V, W and Xs that you're actually interested, the organisation scheme might be technically good, from a data theory point of view: but it's hopeless for creating a practicably navigable music library.

What you need, therefore, is to sub-divide a composer's output in some meaningful way: and I'm going to suggest that you chop it up by the specific 'genre' it belongs to. By this I mean you can listen to pieces by Bach (say) and declare them to be 'an organ piece', 'a choral piece', 'an orchestral piece' and so on. For Britten's output, you might divide the compositions into 'choral', 'keyboard', 'concerto', 'vocal', 'opera', 'radio & film' or whatever other musical sub-division makes most sense to you.

I've prepared a list of the broad genre classifications I would recommend in another article. The proposals aren't academically rigorous: I'm not proposing you split your opera seria from your opera buffa, for example: just 'opera' as a broad classification is more than sufficient for all cases that I can think of! In short, we're not trying to prove how musicologically educated we are: we are simply trying to minimise the amount of scrolling that has to take place when we want to play a specific piece of music.

Of course, this introduces a new element into our proposed 'primary key of recorded classical music': we're now up to Composer + Genre + Extended Composition Name + Movement Number

It allows you to click Bach → Cantatas and now you'd swiftly be able to find BWV 67, because it's not embedded in a list of 1000 other compositions, but appears in a list of only around 220 cantatas. Adding the genre into the mix isn't technically needed to uniquely identify a specific recording, in other words… but it makes it practically a whole lot easier!

Now, you will probably have worked out already that the genre is merely 'derived information': if you tell me the composition name is 'String Quarter No. 3', I already know it's a chamber work, without that needing to be spelled out. If you say it's a 'Violin Concerto', then the fact its genre is 'concerto' is a bit of given, too! Data purists would therefore correctly contend that the music's genre should not be part of a primary key, since it's dependent on something that's already there (namely, the extended composition name). Purity must go out the window, however, when practical considerations arise: and in this case, the need to 'chunk up' the large output of certain composers into manageable sections outweighs concerns about the derivative nature of the genre data item. So genre stays in!

But surely I've just made our primary key four data items long again… and earlier I was crowing about how good it was that I'd got it down to three! Isn't the extra data item going to break lots of music players?

No, is the short answer to that, and to explain why, take a look at this screenshot:

The list on the left-hand side of the screen is handling the first three of our primary key requirements: composer name is displayed first. Within that, we see different genres. And within the Symphonic genre in this specific case, we see the various compositions with their extended names (including the name of their conductor). But how is the fourth element being handled? Well, look on the right-hand side of the screen. The individual movements of a selected symphony are listed in track (i.e., movement) number order.

Most media players will do things this way: the tracks within a selected recording will be displayed in one area of the screen, ordered and sorted by 'track number'. How you get to a specific recording is usually handled in a different part of the screen which is ordered, grouped and sorted by the first three components of our primary key.

So, Composer → Genre → Extended Composition Name → Movement Number will work perfectly well in all known music players on all known conventional operating systems (proprietary hardware using restricted displays and unusual ways of accessing music have their own ways of doing things, so all bets are off for them!). Three of the primary key components are handled in one part of the program display, the fourth is handled in another part. Organising your recorded music in this way, therefore, provides a highly functional, flexible, scalable way of allowing you to access any particular piece of music in seconds.

The reason it does so is because it's based on a good data model: working out what minimum pieces of data are required to get to a specific recording of a work, taking into account the practical issues of having to work with a media player that does things certain ways, and also keeping in mind the practical difficulties associated with wading through huge numbers of compositions that certain composers wrote in their busy lifetimes.

9.0 But what about all my other data?!

At this point, there's a certain inevitable concern that creeps into some people's minds: if you've reduced my music library down to just four pieces of unique data, how do I find music in the key of E flat? Or how do I find all the recordings of Galina Vishnevskaya? Or, how do I see and work with <list some obscure piece of recording-iana here>?

The answer is fairly simple: the primary key of a piece of data is merely the shortest way of accessing everything else about a piece of data, distinct from any other piece of data. It's not, in itself, the only data that exists about that entity.

By way of analogy: the row number and column letters in your spreadsheet aren't the data you're really interested in, are they? They're simply the piece of data you use to quickly find and locate the data you're actually interested in. “Where are the sales figures for the Consultancy division for 2018?” is the question: “Row 67, column G” comes back as the answer. 67G isn't, then, a piece of information of value in its own right, but merely the 'address' where you can find the information which is valuable.

The same is true in this scheme of finding recordings of music. “Beethoven, Symphonic, Symphony No. 5 (Karajan 1962)” is merely the key to finding the four tracks or movements that make up that recording. That the piece was played by the Berlin Philharmonic is not an unimportant piece of information, but it's not the way you organise your music library or make one recording identifiably distinct from another. It's a piece of data that you fetch whenever you supply the 'primary key' data elements. Which is to say, click through composer, genre and extended composition name, your music player will display the tracks that belong to that specific recording -and each track will have additional data embedded within itself which can be inspected (or searched for).

The other data you might want to store about a piece of music is generally quite highly unstructured text. That it's in C minor; that the recording engineer was John Culshaw; that it was recorded on a Saturday morning after a big night out the previous Friday: all of this stuff can be recorded if you want it to be. Generally, however, I would personally only really want to store the full details of the performance or performers for any recording: remember, at this point, we've only got the surname of one 'distinguishing artist' recorded as part of the composition name. How about mentioning that the Oslo Philharmonic is playing, that Ben Titmarsh is playing the flute, and that Jeremy Twiddlethorpe is singing the solo treble part, for starters?

The key thing to understand at this point, however, is that this sort of information isn't as “significant” to a music player as the four pieces of information we've declared to be the 'primary key' of recorded music. The composer, genre extended composition name and track number data items are crucial to finding the music in the first place, so they are necessarily highly structured and standardised data items. By this I mean you don't want to type the composer's name as “Beethoven” for one recording and “Beethoven, Ludwig” for another -because now you have two data items describing the one composer, and that means you'll have two things determining a sort/grouping order. Functionally, it means your music player will list Beethoven's music in two completely different places, which destroys the concepts of discoverability and functionality we're aiming for.

So, those 4 primary key data items need to be entered and stored in a highly consistent manner (though you get to decide on what that consistently-used format should be, of course).

But everything else is pretty much just free-form text, with no requirement for rigid rules and consistency. Want to call it the “BPO” for one recording and “Berlin Philharmonic” for another and “Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra” for a third: be my guest, in the sense that no-one will stop you doing it and no fundamental music-discovery process will be harmed by you doing it.

Except… if you're the kind of person who ever approaches their music collection and idly wonders, “I wonder if I've got a recording that involved Herbert von Winkleman playing flute with the Berlin Philharmonic, you're going to get into trouble if you have been inconsistent with how you entered data about which orchestra was playing. It's easy to do a search in most music players for “Berlin Philharmonic”, for example. But if you've entered the crucial data as “BPO” on the one recording you've got of Winkleman playing flute, you're search isn't going to find it!

For this reason, whilst it's not a strict requirement to type in non-key data in a highly structured, organised and consistent fashion, it makes practical sense to try to do so.

For myself, I only ever record four things about a recording that aren't in the already-mentioned primary key: Full conductor's name; Orchestra's name; Choir's name; Soloists name and roles.

Obviously, not every recording will feature a Choir; chamber works will not feature a conductor, choir or orchestra! So I might not type in every one of these four items for every recording, but when I do, they'll be in that order and I'll try to be consistent about it: if it's 'Wien Philharmonie' on recording, it won't be 'Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra' on another, for example.

And where do I type these extra pieces of lightly-structured free-form text? There aren't many places offered by most tagging software where large amounts of free text can be typed comfortably. Take this screenshot, for example:

That list of performers you see at the bottom of the screen is quite long (234 characters long to be precise). It could have been typed into any of the displayed fields (apart from the four associated with the primary key, of course!). I've chosen to stick it in the COMMENT field. Why not use the LYRICS area, which is just as big? Because most music players will display comments (though some will have to be configured to do so). Many will not display lyrics. It's as simple as that, really.

Why not stick it in the PERFORMER field, which seems ideally named for it? Three reasons, really.

First, it is displayed in this particular software as quite a narrow field. That doesn't mean PERFORMER can't store 234 characters or more of data: there's no practical limit on what any of these fields can store these days. But if only a small part of it is displayed at a time, it will be difficult to type it in or read it back.

Second, a lot of music players will display and search COMMENT tags: it's a 'standard' tag that most media players expect to find. LYRICS and PERFORMER are not quite so standard, and a lot of media players simply won't know they're there in the first place.

And third (and possibly the most important): it really doesn't matter what your tags are called. Every single tag in a FLAC file is simply a key-name=value pair. None have a formal data type associated with them. I mean, for example, that though there's a tag called “DATE”, if you choose to type the word 'violin' in there, no-one will stop you doing so. There is no external validator looking at what you put into your tags saying 'that's not the sort of data you should be entering there!'. So, you type in the data that's important to you in whatever field (i.e., tag) that your favoured music-playing software presents and uses in the most effective manner, keeping in mind as you do so that what your favoured music-playing software is today might be different tomorrow!

This last point is important too. Clearly, Clementine likes to display COMMENTs in large areas of text. It was my daily driver as a media player. So I'm happy… for now. The real question to ask yourself, however, is do other media players and software work similarly. If they do, then Clementine isn't just being unique and peculiar, so playing to its particular strengths today won't screw you over if you ever switch software in the future. So, is Clementine unique in the way it handles the COMMENT field? Well, here's dbPoweramp on Windows:

Notice how long the 'Comment' field is at the top right-hand corner of the program display area? In fact, it appears to have no end, just running directly into the right-hand edge of the program display area without a pause. Practically, it really does accept any huge amount of text you type into it. But notice that all the other data fields are formally limited in size: they will certainly accept long data entry, but its display will be truncated, making viewing it all (and thus inspecting it and editing it into shape) problematic.

Here's another example, using a piece of software called TagScanner:

Again, spot that large area for free-form comments over on the right-hand side of the screen; spot the very-tightly constrained sizes for all other tag fields, too. So a pattern emerges that a lot of audio-related software expects COMMENT to be long and full of data that needs to be displayed in large, long fields, not short, little ones.

On the other hand, it doesn't always work that way, of course. Here's MP3Tag, a very popular tag editor on Windows:

Note that in this software, the COMMENT field is strictly size-constrained like all the others -and in consequence, the display is severely limited and clearly runs off to the right of whatever the program manages to display. Again, this doesn't mean the program can't actually store long data in that field; it merely can't display all of it at once.

So the point is that software is varied and does different things in different contexts. So it's possible that telling you to store a lot of data in COMMENT might not be right for you and your particular choice of software -but it's the only tag that a lot of software displays in large format and it's one of the 'standard' tags that nearly all software can display and search in, without lots of re-configuration effort required. So my recommendation stands!

Accordingly, my four non-primary-key pieces of data about a recording (conductor, orchestra, choir, soloists) are always entered into the COMMENT field for each music file. I naturally suggest you do likewise -but feel free to add other bits of data into it, too, that you find useful to know about a recording.

Once that sort of non-key data is stored in the COMMENT field, most music players will let you display it if you want to -or at least search through it and filter by it if you need to. Once you've recorded “John Thistlethwaite (oboe)” in a COMMENT tag for a recording, you'll be able to search your entire music collection at any point for any recordings on which Mr. Thistlethwaite ever played.

10. A final thought about non-key data

For my own recordings, the COMMENT tag only ever stores the four pieces of non-primary-key data I've already mentioned a couple of times: distinguishing artist's full name, orchestra, choir and soloists. Some people insist on storing all sorts of other data they might find interesting about a recording, though… such as recording engineer, location, record label, record label's catalogue number and so on.

My first response to this is: don't do it. A recording may once have been released by Decca, but is now on Philips, because both are owned by Warner: record label is a meaningless way of finding or organising music to play! I'd same the same about all the other items I've mentioned too: would I ever sit at my PC and say, “Hmmm… I feel like listening to something John Culshaw was the recording producer on?” No, much as I revere the man. So it's pointless storing that data inside your digital music files.

My second response is: your music files are not the only source of information in the Universe. If you are ever sat there wondering what wonderful recordings Culshaw produced, you can look it up on Wikipedia. There's no point over-burdening your music files with amorphous data which can better be found online or, dare I say it, in the CD booklet!

So, my strong advice is: don't try storing this stuff at all… but if you absolutely insist on it, you should find yourself a music file tagger that permits the use of Custom Tags, and load the data into your music files that way. Don't overburden the COMMENT tag with all this extra stuff, in other words, but find distinct homes for the data in other tag fields. You'll find, for example, that my own Semplice tagger permits up to 9 custom tags …though the data, once stored in these extra tags, tends not to be display-able or search-able by any music player I've ever known. Meaning, again, that I personally would consider it a waste of time to store this stuff in the first place!

11. Universality

Do these music tagging suggestions apply universally? They surely do, though that doesn't mean they will necessarily and always apply to your very special and particular way of interacting with your music collection! People are unique, of course, and so it's entirely possible you interact with music in a unique way that this proposed organisation scheme cannot possibly accomodate.

Whenever I've been dealing with people who say, 'Oh, your scheme won't work for the way I listen to music', however, almost without fail, it will turn out that they are using a specific piece of audio hardware; or that they don't actually know fully how their music software works and have thus accommodated themselves to its 'failings' without understanding that those 'failings' are trivially worked around. On at least two occasions, I've been told 'your scheme won't work for me', only to find out that on both occasions, it's because the individuals concerned can't actually be bothered to tag up their music at all! For sure, if you can't be worked up enough to tag your music files properly, then no organising scheme on Earth can help you out of the hole you've dug for yourself!

But, assuming you are using standard desktop computers or mobile phones; assuming that you care enough about your music to want to organise it efficiently and effectively in the first place; and assuming you are therefore prepared to put in a little effort in assigning appropriate metadata tags to your digital music files… then, yes: the scheme I've just outlined above will and does apply universally.

By that, I mean, these ideas will work for every music player I know about, on every operating system I've ever used, and one's access to your music will remain fast, efficient and effective on all of them. The fundamental reason for that is simply this: the data model is sound: correctly and technically identifying key-data and distinguishing it from non-key data is the crucial ingredient here. If the data model is sound, it will be portable across players, devices and operating system environments, without drama.

Remember that all music players display music in a default way: the use of a 'primary' key as I've suggested here will ensure that your music is always sorted in composer/genre/extended composition name order, which is the natural way to identify any one recording distinct from any other. Most music players of my acquaintance will default to this sort of sorting/grouping order out-of-the-box, or with a very little bit of re-configuration. Hence, what information theory says is the most efficient way to retrieve a specific recording turns out to be the 'natural' way most music players are configured to organise things, too. (Coincidence? Not, I would say!!)

Remember, too, that if you expect to be able to find music by ways that aren't the “natural” way, that's entirely fine too. A proposal to order data one way shouldn't interfere with your rights and ability to access data in other ways. The fact that you can only order data in one way, but that there are an infinite number of different ways to access data, inherently and implicitly means your music playing software must offer the ability to search comprehensively through all your tags, rather than just stick to displaying information sorted by a handful of them. Fortunately, the bar is quite a low one to clear: provided your music player allows searching the COMMENT tag, and also provided that your non-key data is stored coherently there, then you'll always be able to use the media player's search functionality to filter your music collection by it.

Of course: if you're using some obscure audio playing/management software on a hardware platform I've never used to achieve something other than fast access to a specific recording, these proposals may well not apply to you. That makes you the 1% exception that otherwise proves the rule, I'm afraid. I wish I could meet your exacting and unique standards, but if the above doesn't do it for you, then you really are on your own. (Which is a polite way of saying, if you insist on fighting basic information theory, I can't help you!)

12.0 Conclusion

For some reason that I have yet to understand, the topic of how best to tag classical music tends to engender a lot of heat and anger rather than light! I think it's because what I've documented here seems to be telling people “you've been doing it wrong all these years!” and they get somewhat defensive as a result.

And, to be fair: I probably am saying they've been 'doing it wrong' to some extent. In my professional data management opinion, the tagging/sorting/ordering scheme I've outlined here is the only natural one available -and it happens to be extremely efficient and scalable, too -because it seeks to specify the minimum data elements required to achieve a unique 'hit' on a specific recording of a specific composition. It's because it's soundly based on information theory principles that it works so well: but you needn't care about them, just the fact that your huge music library is easily navigable and highly discoverable.

In short: I commend the Composer/Genre/Extended Album Name + extensive use of the COMMENT tag to you, anyway… and look forward to hearing from you if it fails your specific needs.

In a second article, I examine in much more detail the sorts of things that affect what you put into the various FLAC metadata tags that are available to you in more detail, but I think this article has outlined the general principles enough to be going on with for now